Decision Making: A Three Part Series

How to Create a Decision Making System

In last week’s newsletter, I made it clear Strategy is a set of specific choices or decisions.

This week begins a 3-part series on how to make those decisions by creating a “Decision Making System” to ensure you align your Strategy to your Operational Execution.

First a quick story:

Around 2012, 20 years into my career, I realized I had my own personal decision making algorithm. One day at Mozilla, after about a dozen interruptions all asking, “Hey Jim, I need a decision!” I realized my responses were mostly on auto pilot asking everyone the same 7-10 questions in order to either help them decide or to help me decide.

We were in high growth mode at Mozilla and most of these decisions were for unplanned purchases, unplanned hires, Legal, HR, or facility issues… all the areas that reported to me at the time. My personal algorithm consisted of questions such as:

“Is it in budget?”

“What other options did you consider?”

“Why do we need this now?”

“Did you get multiple quotes?”

“Benefits vs risks?”

“ROI?”

“Trade-offs vs planned spending?”

It was immediately clear this kind of manual and especially verbal decision/approval system wasn’t scalable so I began the initial designs of building a better “Decision Making System” based on my 7-10 questions… my “personal decision making algorithm.”

I made a call to a good friend and former colleague I worked with at both ISN and Netflix, Delly Tamer, Founder/CEO of Biztera, where he and his team were building similar software. Over the course of the next 3 months, we built version 1.0 of Mozilla’s decision and approval system. We named our system CASA (contract approval and signature authority). CASA is still in use today at Mozilla (10+ years later) as an automated request and approval “decision making system” for several request types including purchasing requests, hiring requests, security and IT requests, facility/workplace requests, and legal requests.

Version 2.0 and many versions thereafter built reporting insights into our Biztera/CASA software database which had now collected critical answers and key assumptions surrounding various operational decisions. We quickly realized we had a treasure trove of “decision data” and “decision assumptions” allowing us to course correct future decisions.

Wherever you are in your own internal decision making “algorithm” or decision/approval systems journey, over the course of the next few weeks I’m going to share with you my “Best Of” learnings from creating and managing Decision Making System(s) including key frameworks and actual templates you can customize for your own use.

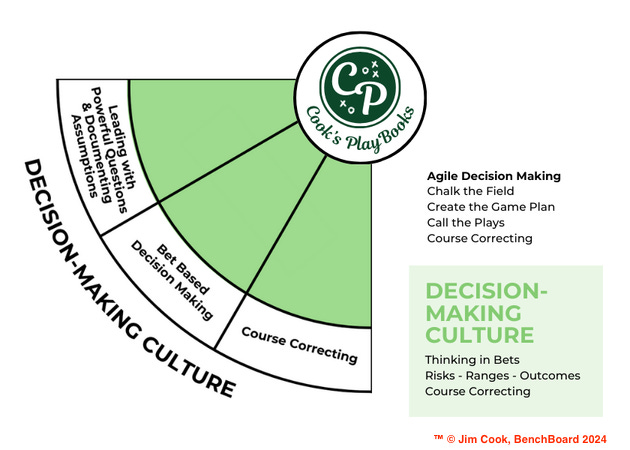

Here are the cliff notes to this 3 part “Decision Making” Series. I’ll be covering Part 1 today and Parts 2 and 3 in the following weeks.

Part 1: Decision Audit and Decision Scorecards

Let’s start by taking a critical look at your current decision-making processes. Who makes your critical company decisions? Why do they make them? Who else could make them? Part 1 will also explore the power of score-carding your decisions - a method for documenting clear criteria in order to make a decision and to measure success or failure after the decision is made.

Part 2: Decision Timing and Course Correcting

Timing is everything when it comes to decision-making. Part 2 will identify strategies for recognizing decision windows, balancing urgency with due diligence and properly playing on the risk curve of a decision. Here I will make it clear that no decisions are perfect and 100% of decisions should be “course corrected.” Whether we call a course correction “continuous improvement” or “pivoting,” Part 2 will focus on tactics for analyzing decision assumptions vs actuals and pre-wiring course correction decisions and ultimately creating a decision culture that embraces agility.

Part 3: Decision Communications

Effective communication is the currency of your leadership. Part 3 will provide specific templates for how to best document and communicate your decision making system and by doing so lead with transparency and alignment across teams, your board, and investors.

My ultimate goal is to provide you strategies and tools to help you make higher quality and higher velocity decisions, how to course correct, and how to communicate decisions to increase the currency of your leadership.

Subscribe now to make sure you receive all 3 parts of this Decision Making series directly into your inbox.

PART 1: DECISION MAKING

Audits and Scorecards

When I can’t say it better than others who have already said it, I’ll simply bring you their quotes. Here are two of my favorite “Best Of” passages on Decision Making.

The Quality of Your Decisions is the Currency of Your Leadership - Michael Lopp, Rands in Repose

“The furiosity with which a high-stakes decision arrives tells you two facts and a lie.

Fact 1: Here’s a big decision.

Fact 2: It’s 100% your responsibility.

Lie: You better hurry.

The urgency is often the lie. Everyone can clearly see a big decision needs to occur. It’s also readily apparent that it’s entirely yours to make. This combination of the decision’s magnitude and obvious single ownership creates pressure. Don’t confuse pressure with urgency. Don’t confuse importance with urgency.

This last bit of advice is designed to give you the time you need to check your work. Slowing down gives you the opportunity to ask for all the help. Taking time to think on the most critical decisions, in my experience, is how you build a higher quality decision. By slowing down, I drain the emotion, urgency, and irrationality that often arrive with these decisions, and I’m able to see what’s important versus what everyone is urgently yelling.

Big decisions have a fan club. These are the humans swirling around the decision who care deeply about its outcome. They have contradicting motivations: they know enough about the decision area to call themselves experts, but they are also intimately aware (or annoyed) that it’s not their decision to make.

The fan club grows annoyed when you don’t move with – what they perceive as – appropriate urgency, so I’ll repeat myself: the quality of your decisions are the currency of leadership.

It’s not that you moved quickly, it’s that you invested enough of your time to build a quality decision. You won’t be judged on how quickly you decide; you will be judged by the consequences of your decision that appear in the hours, days, weeks, months, and years after you decide. It is these results that build your leadership reputation.”

____

“What If I’m Wrong?

That’s the question that shows up in the middle of the night for me when considering a big decision. It’s a good question. What if you’re wrong? What will happen when you decide? Wander those pathways in your head and with your trusted peers because attempting to predict the unpredictable is a critical part of this process. You’ll need to explain these potential consequences when you’re presenting your decision to everyone.

That’s when I know I’ve decided. It’s not that I can explain the decision, it’s that I can tell you the story of how I decide, what I expect to occur as a result, and what we’ll do if I’m wrong. And you understand.

See, because I’ve thought it through, it’s becoming a compelling, thoughtful, and defensive story. When I tell those I trust the story, they believe me.”

High-Velocity Decision Making- Jeff Bezos 2016 annual shareholder letter

“Day 2 companies make high-quality decisions, but they make high-quality decisions slowly. To keep the energy and dynamism of Day 1, you have to somehow make high-quality, high-velocity decisions. Easy for start-ups and very challenging for large organizations. The senior team at Amazon is determined to keep our decision-making velocity high. Speed matters in business – plus a high-velocity decision making environment is more fun too. We don’t know all the answers, but here are some thoughts.

First, never use a one-size-fits-all decision-making process. Many decisions are reversible, two-way doors. Those decisions can use a light-weight process. For those, so what if you’re wrong? I wrote about this in more detail in last year’s letter.

Second, most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. Plus, either way, you need to be good at quickly recognizing and correcting bad decisions. If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure.

Third, use the phrase “disagree and commit.” This phrase will save a lot of time. If you have conviction on a particular direction even though there’s no consensus, it’s helpful to say, “Look, I know we disagree on this but will you gamble with me on it? Disagree and commit?” By the time you’re at this point, no one can know the answer for sure, and you’ll probably get a quick yes.

Fourth, recognize true misalignment issues early and escalate them immediately. Sometimes teams have different objectives and fundamentally different views. They are not aligned. No amount of discussion, no number of meetings will resolve that deep misalignment. Without escalation, the default dispute resolution mechanism for this scenario is exhaustion. Whoever has more stamina carries the decision.”

____

Jeff Bezos - One Way vs Two Way Door Decisions - 2015 annual shareholder letter

“Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions.

But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors. If you’ve made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you don’t have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

As organizations get larger, there seems to be a tendency to use the heavy-weight Type 1 decision-making process on most decisions, including many Type 2 decisions. The end result of this is slowness, unthoughtful risk aversion, failure to experiment sufficiently, and consequently diminished invention.1 We’ll have to figure out how to fight that tendency.”

COOK’S GAME PLAN:

Let’s clearly define “Decisions” just as we did with “Strategy” last week as part of our Game Plan.