CFOs - Be the Internal VC of the Business

I’ve written before about a key leadership thought model of mine:

“Make every person in the company the CEO of their function.”

Today, let’s take that metaphor one step further and focus on the CFO.

But instead of thinking about the role as the “CEO of Finance”, I think a far more powerful analogy is:

The best CFOs operate as the internal Venture Capitalist of the company.

The CFO as Internal VC

When you look closely, the metaphor fits.

Inside every growth company, CFOs should be doing what great VCs say to do but fall short of making this mental shift. So this post is here to help you with that.

Your go-forward thought model of the CFO role:

Functional operating plans = Mini Business Plans

Annual and quarterly budgets = Funding Rounds

Cash runway = Managing Each Functions Budget Before Next Investment

Staging & gating of Investments = Rounds of Funding Tied to De-Risking and/or Value Creation of internal investments/projects

Portfolio management = Allocating capital across product, growth, people, and systems

Board updates = Reporting progress against the functions (a.k.a “Dept”) investment thesis

Closed-door CEO sessions = Hard conversations about doubling down, pivoting, or stopping with the Function/Dept Leader

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

As CFO, stop thinking your job is to manage the money. Start thinking of yourself as the Chief Investment Officer with a key shift in framing or deploying your precious cash against a portfolio of internal bets.

Mini Business Plans, Not Just Budgets

In this model, budgets stop being static spreadsheets.

Each function (dept) effectively runs a mini business plan:

Clear objectives

Defined investment ask

Expected ROI tied to company strategy

Time horizon for results

Leading indicators and lagging metrics

Now, as CFO (ahem “internal VC”), you are no longer approving spend - you are now underwriting the investment thesis.

Funding, Runway, and Time-to-Value

Great investors and Great CFOs obsess over cash runway.

When you focus on this internally at a company, the question is not “How long until we run out of cash?” but rather:

“Do we have enough cash runway for this investment to actually work?”

Or

“Has the capital we’ve allocated to this investment thesis been used to de-risk the next milestone and has the investment created value?”

Or

“What’s the payback period for this internal investment?”

Killing good ideas too early is just as dangerous as funding bad ones for too long.

The best CFOs sequence investments, stage funding based on hitting key milestones, create value, or de-risk a few key pillars of the long term investment thesis.

As CFO, you are an investor. As CFO, start playing internal VC.

Staging, Gating, and Reallocation

Internal VCs don’t fund everything all at once.

They:

Stage capital

Set key milestones (investment gates)

Fund according to progress

Reallocate aggressively

This is where great CFOs separate themselves from finance operators.

Stop asking, “Did you spend to plan?”

Start asking, “Is this investment earning the right to more capital?”

Metrics as Investment Reporting

In this model, metrics become investment reporting, not performance dog-and-pony theater.

Each function reports:

Cash spent against key projects (P.S. - “keep the lights on” is a key project)

Returns generated (ROI)

Risks emerging

Confidence levels to convince you the investor/CFO to fund their next tranche

This reframes accountability in a powerful way. Leaders stop defending budgets and start defending ROI and start pitching you.

The CEO Relationship: Closed-Door Truth

Every great VC has private conversations with the founders and CEO

So should CFOs.

Closed-door CEO sessions aren’t about spreadsheets. They are about relationships, judgment, and next-step strategy.

Which bets are working?

Which need more time?

Which should be stopped?

Where to double down?

Want to Be a VC Someday?

I used to think I wanted to be a VC. No longer. But if you do, there’s nothing wrong with that (he says tongue in cheek).

If you want to be a VC someday and operate at that level of strategic influence, then start acting like one… tomorrow.

Be the chief allocator of cash for the company.

Think in portfolios, not departments.

Act like every dollar has an opportunity cost. Hint - it does.

Your job is to compound valuable bets over time. Hard stop.

The Investor Mindset of a CFO

Let’s double click into the Investor Mindset. Here’s a hot take: every strategic decision a CFO makes is, at its core, an investment decision.

How much to allocate to R&D to build tomorrow’s product?

How much to invest in marketing to fill tomorrow’s pipeline?

When to hire the next executive leader who can scale a function or open a new market?

Each decision requires a strategic forecast of returns. Each decision requires “thinking in bets”.

Every “next decision” should therefore be adjusting the probabilities as more information is learned from the original assumptions.

The best CFOs think in time horizons and portfolio risk. They manage today’s spend while creating optionality for tomorrow’s growth.

They ask:

“What’s the expected ROI on this decision, and what’s the risk-adjusted payoff if I give it the right runway?”

Allocating Capital Like a Pro Investor

A great CFO runs the company like a balanced investment portfolio.

Every line item - product development, go-to-market, operations - is a category in that portfolio. The CFO’s job is to size each investment according to its expected return, its risk, and its correlation to everything else.

Too much in R&D, and you risk running out of cash before product-market fit.

Too little in R&D, and your product stagnates while competitors out-innovate you.

Too much in marketing, and you risk wasting dollars before product-market pull.

Too little in marketing, and your pipeline engine sputters just as you start achieving product market fit.

It’s the CFO’s version of portfolio rebalancing. You should always be adjusting your internal investment mix to maximize future returns without overexposing the business.

No, it’s not easy. It’s complex. It’s a balancing act while constantly juggling 3 or more assumptions in the air.

The CFO’s Dual Mandate

Unlike fund managers, CFOs don’t get to just invest other people’s money.

They have to protect the cash runway while investing for the future.

That means managing the tension between:

Cash preservation and revenue growth acceleration

Short-term burn vs. long-term compounding of company value

Operational discipline vs. strategic risk-taking (making better bets)

Great CFOs have learned after multiple trials and errors on how to better sequence investments, when to lean in, and when to pause or hold so the company never has to abandon a compounding bet too early.

Great CFOs build plans that give good ideas enough runway to prove out their returns, instead of pulling the plug too early or too late. They’ve learned how to balance and “stage and gate” for the next set of investments.

Investing in Leaders

Finally, the best CFOs don’t just invest in projects and vendors. They invest in people.

Throwing cash at stuff doesn’t create returns. Leaders who regularly make increasingly better decisions are what creates value.

A CFO’s highest-leverage investment is in hiring, developing, and empowering the leaders who can own their respective budget lines and turn them into high-ROI engines of activity.

When you hire the right leader, your capital allocation multiplies. When you hire the wrong one, even the best investment strategy burns cash.

That’s why the most successful CFOs think like venture investors:

“Where’s my best next bet; My bet for product, people, and executional systems and processes?”

From Finance to Investment Thesis

If you view your company through the lens of investment returns and your time horizon through the lens of compounding returns, you start making better decisions.

You begin to act less like a budget enforcer and more like a portfolio architect. You begin to be respected for allocating the company’s capital properly to maximize everyone’s enterprise value.

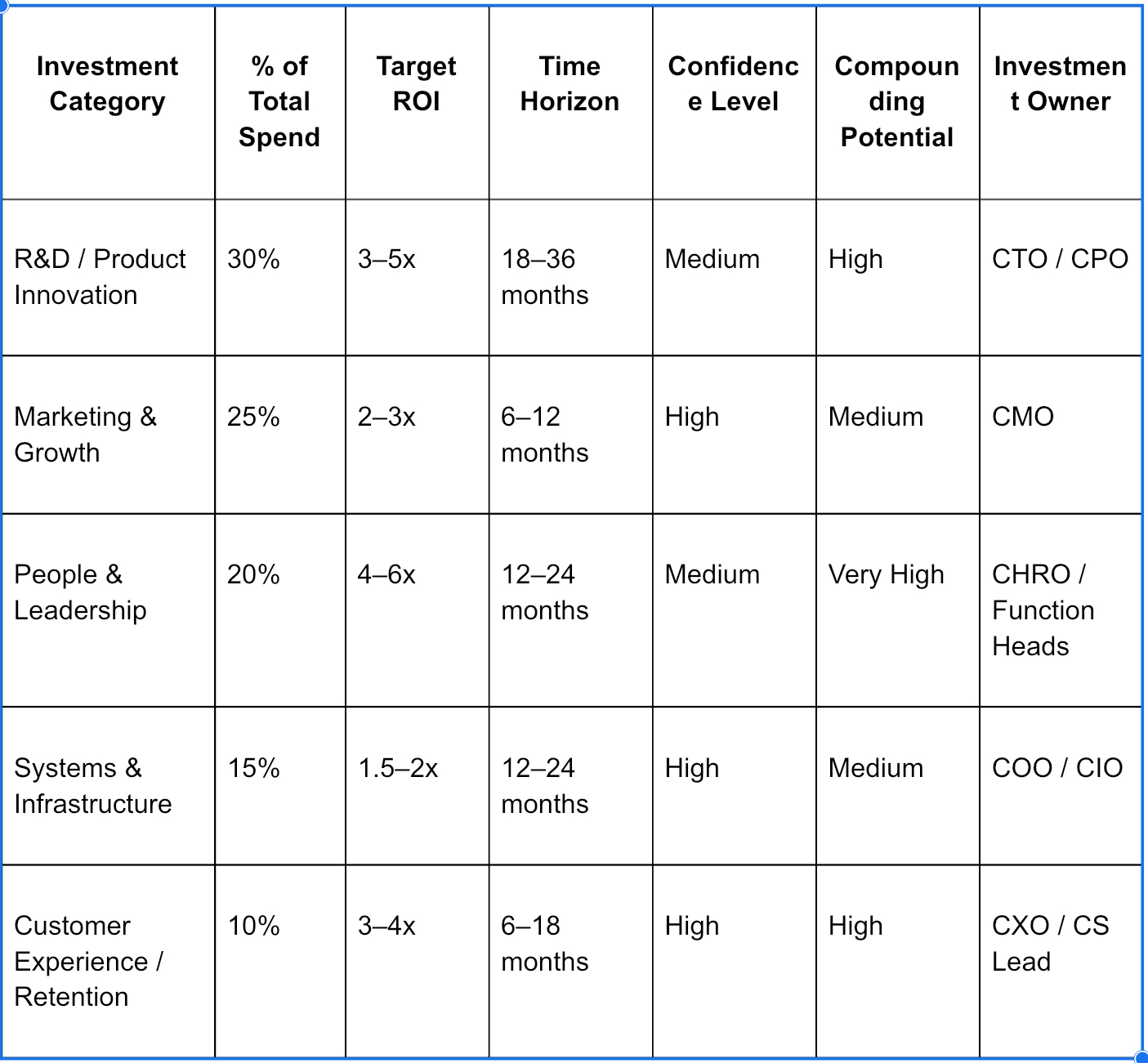

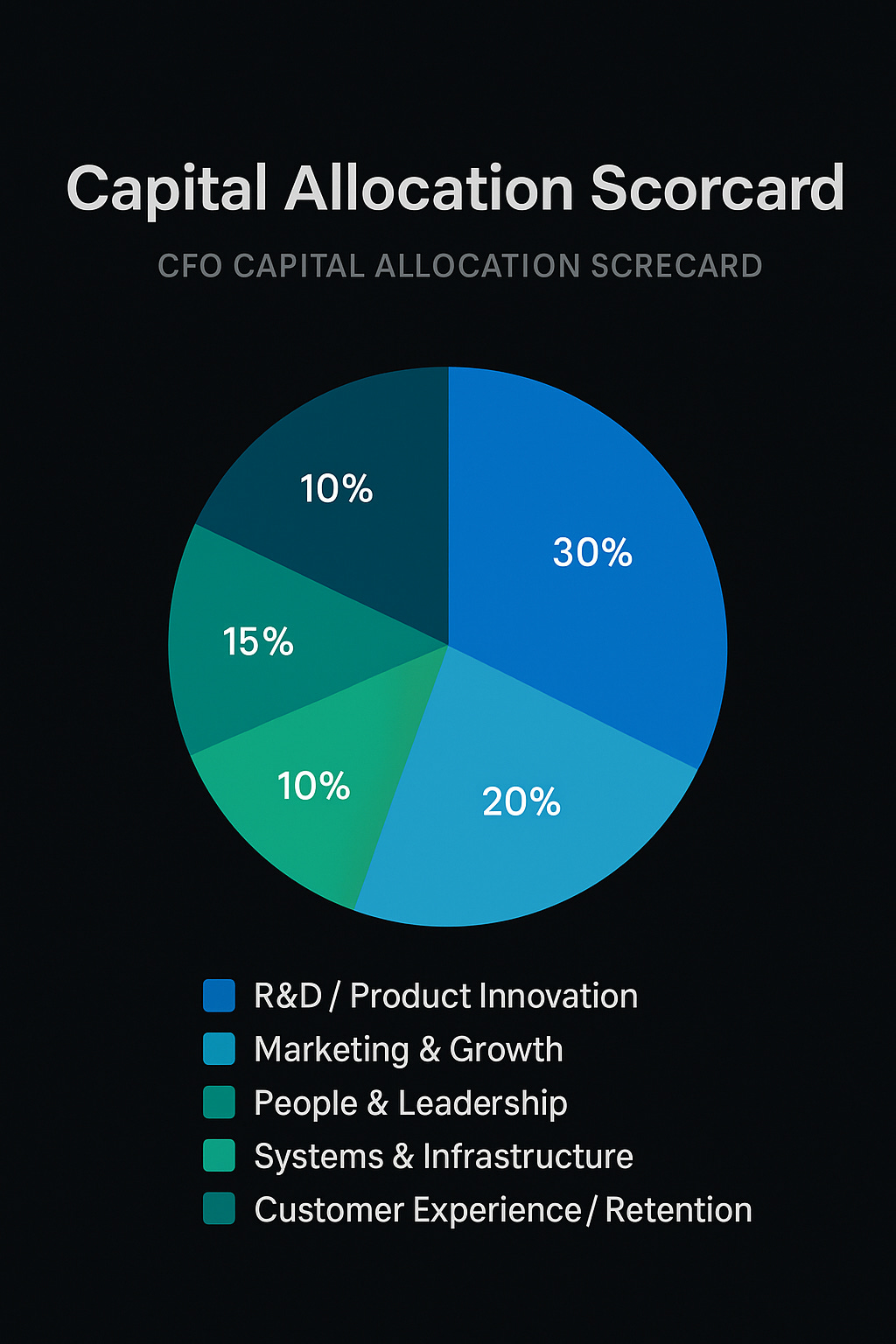

Capital Allocation Scorecard: The CFO as Portfolio Manager

I banged this out as an example “portfolio manager”. YMMV - “your mileage may vary” - but it’s the framework that counts. The Investment Categories are your “stocks”. You only have so much cash to invest.

The next time you start struggling to communicate as a CFO… take a pause and reframe your communication around:

“What” you recommend investing in.

Why?

When? - think about your own investment portfolio and it just might unlock you.

Now start thinking about diversifying and balancing your “bets” (a.k.a investments) properly.

Align your Whys, Whats, and Whens to your clear financial philosophy (Your “Thesis” - Yes “Lead with a Thesis” - I wrote that post 2 weeks ago).

Your peer executives may disagree with your thesis but at least you’ve now established a proper investment framework and decision-making guardrails as you seek to align everyone’s budge/investment requests.

Finally, no matter where you or your exec team finally land on the risk/reward curve, don’t forget to be explicit about the Cash Runway tradeoffs and risks of the bets you’ve all just aligned upon.

No decisions or investments are free. They all have varying degrees of risk and ultimately impact the value of the company in the future when you need to raise capital again.

You are therefore trying to balance and de-risk the value you’ve created at that future point in time vs the bets/investments you made historically.

You aren’t just operating other people’s decisions (your CEO’s or your Exec Peers’). You are their portfolio investment manager and you must coach them on the risk/reward tradeoffs, the upsides if you are right, but especially the downsides if you are wrong.

You must cut your losses as early as possible and you must reinvest (double down?) on the decisions that are working.

You must rebalance your portfolio at least annually but in reality in startups - this is at least semi-annually.

The best CFOs aren’t just keeping score and reporting. You are the Chief Investment Officer and your scoreboard is the value you’ve helped create through your smart investing during the next fundraising period.

Be the internal VC of your company.